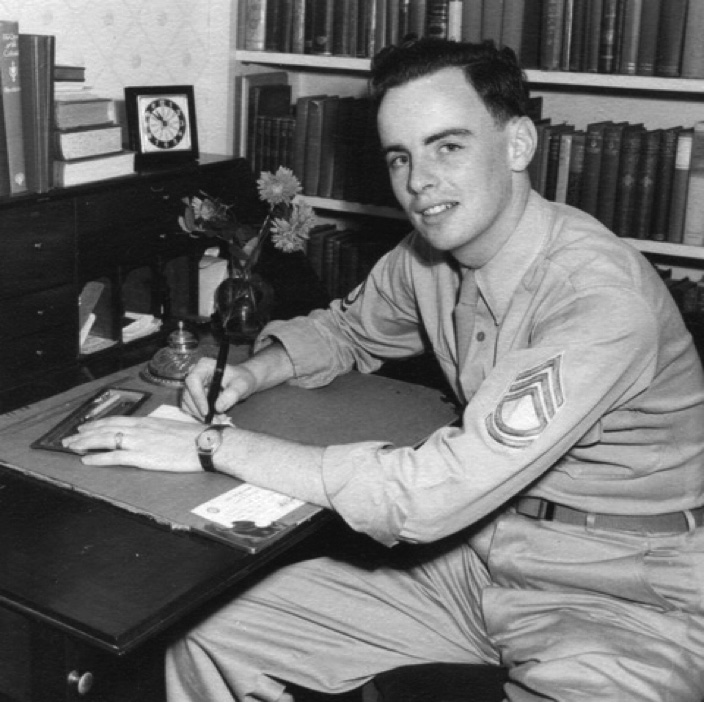

CHARLIE WILLS stateside in 1945 just before his discharge, after completing his 35 missions against Hitler and his allies. (Courtesy Photo)

By HELEN BREEN

LYNNFIELD — Legendary Lynnfield homebuilder Charlie Wills, who died in May at 101, left a detailed account of his military experiences at the end of World War II.

In 2021, Charlie and his wife Arnie moved to Edgewood, a senior living community in North Andover. He soon became active in the Men’s Club. When Charlie’s turn came to share his story with the group, he hesitated because his voice had become compromised as a result of a stroke.

Then Charlie remembered that in 2001, he had made a recording about his military service when he flew 35 missions as a radio operator over Nazi Germany and other enemy targets. Historian Stephen Ambrose had requested the recollections of veterans for his book, “The Wild Blue: The Men and Boys Who Flew the B-24s Over Germany.” Hundreds of veterans responded. Their names, including Charlie’s, are listed in the book’s “Acknowledgments.”

Charlie retrieved the recording he had sent to Ambrose. His daughter, Cynthia Harriman, then made a transcript of it from which they selected passages describing his tour of duty. Even as Charlie passed his 100th birthday, his remarkable memory, recordkeeping skills and trove of old photos made the task easier.

In a matter of weeks, the father-daughter team had created a 30-minute video in which Charlie’s own voice narrated his experience.

Training

In November 1942 at age 18 as a sophomore at the University of New Hampshire, Charlie joined the Army Air Cadet Program. He and his buddies were hoping to finish college before being called, but they could only complete their fall semester.

Charlie was then sent to Atlantic City for basic training, followed by a stint at the University of Vermont. He surmised that the cadet program had a backlog of draftees at this point. He was then assigned to Nashville, where he started his training as a radio operator. Next was Sioux Falls, South Dakota at a huge military instillation facility where recruits trained around the clock. There, he learned to take radios apart, reassemble them and master Morse code.

Gunnery school followed in Yuma, Arizona. Charlie recalled that they started with skeet shooting “to teach us to lead the target.” Proudly, he received his gunner wings and corporal stripes before earning a 10-day furlough home. He then reported to Westover Field in Western Massachusetts. Charlie enjoyed the USO activities there with the local girls, and was able to drive home on weekends for the four to five week duration.

After 18 months of preparation, Charlie and the other airmen were ready for action. At Chatham Field in Georgia, they were assigned to crews consisting of four officers and six enlisted men. Soon they were whisked to Grenier Field in New Hampshire for their trek to the European Theater. To avoid submarine threats in the Atlantic, the passage took days — touching down in Newfoundland, the Azores, Marrakesh and Tunis before arriving in Puglia, Southern Italy.

Just lucky

The airfield from which Charlie’s team would sortie into Nazi Germany was San Giovanni Field, near Cerignola in war-torn Italy.

Men had to complete 35 missions before their tours were over. Charlie attributed his survival to the delays in his stateside training, and to the skills of his 24-year-old pilot Lou Dolan. “Jerry,” as Americans referred to their Nazi foe, was literally running out of gas, thanks to the lethal attacks of previous units.

Charlie’s Combat Flight Record, 740th Bombardment Squadron, lists those 35 runs that he survived to destinations such as Trieste, Bologna, Vienna, Munich, Pilsen, Regensburg, Krems, and “the Adriatic.” He and his wife Arnie would visit many of these European cities years later.

Fortunately, Charlie’s squadron survived without incident, but these young men did not know that as they mounted each flight with silent trepidation. The group also benefited from improvements in gear and equipment made at the end of the war. New flight suits were heated electrically, including jackets, boots and gloves. Radar had just been introduced. Now they could see through the clouds. And having their guns mounted on swivels saved having to open widows when aiming at targets from 20,000 feet.

The officers and crew were awarded the Air Medal for their first five missions, and an “Oak Leaf Cluster” for each five missions thereafter. They also received “battle stars” for participation in the European Theater. The men counted their flights carefully, from the first one on Oct. 8, 1944 to the crucial 35th mission on April 2, 1945. Charlie admits there was a bit of “hell raising” after that last flight.

Charlie’s squadron sailed home on the converted cruise ship Mariposa, passing Gibraltar two days before Victory in Europe Day on May 8, 1945. They landed in Boston at Commonwealth Pier. By VJ Day, Charlie was processing discharges in Tennessee. He soon reported to Westover Air Base in Massachusetts for his own discharge.

Charlie returned home, married Arnie and raised four children in Lynnfield where he and his partner, Roger Harris, built some 388 homes.

But Charlie did have one more flight. In 2001 at age 76, he flew in an “All-American” B-24 over Fort Meyers, Florida for a charitable contribution.

The video

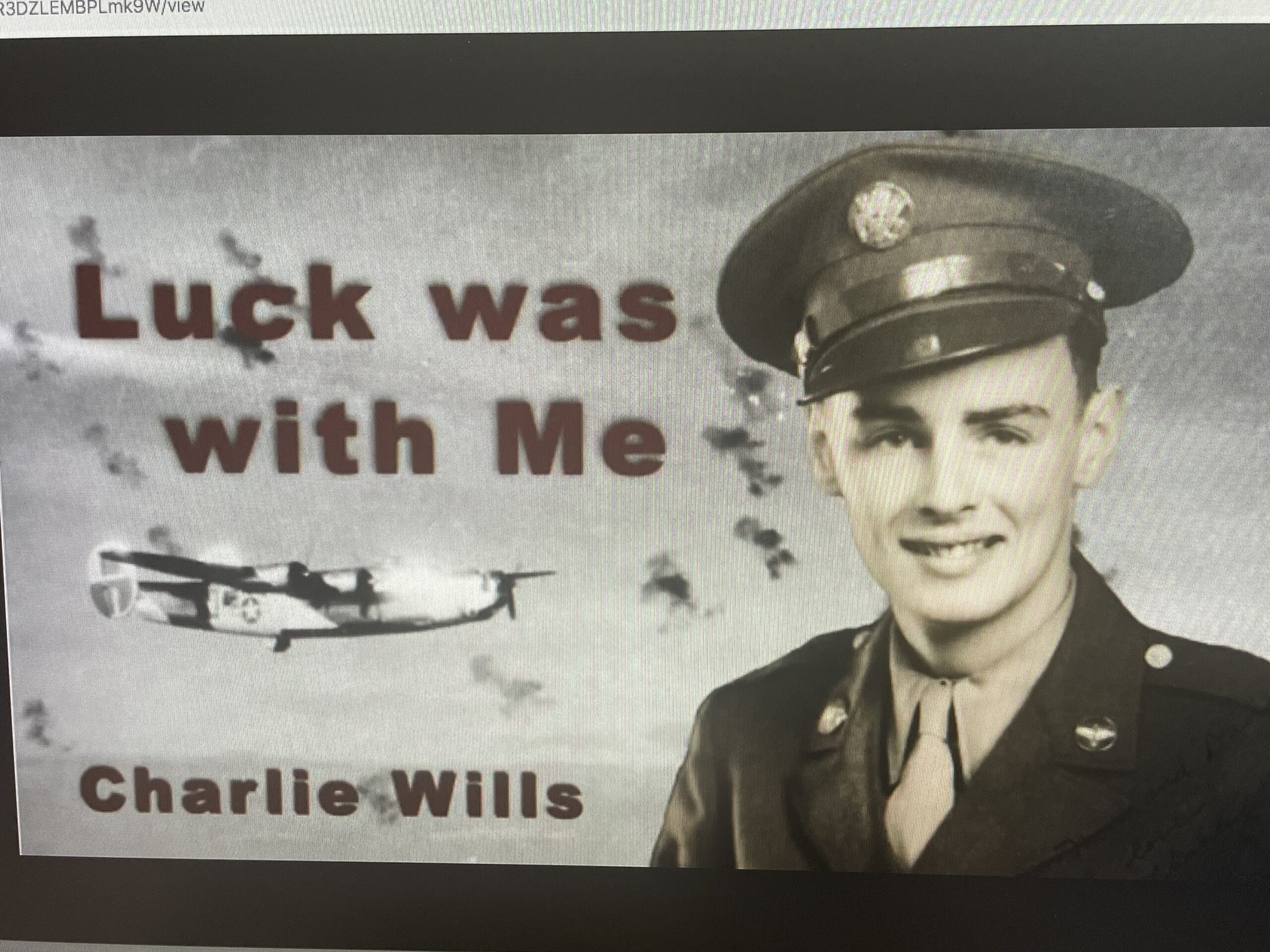

Flashing throughout Charlie’s video was the word “lucky” encased in an exploding cloud. That word set the tone for Charlie’s reflection on his World War II experience.

Years later, his daughter Cynthia asked him if he thought the war had affected his life. He replied: “I can’t say it did. Going to war was just what everybody did at the time.”

Then Cynthia added: “That was pretty much Dad’s philosophy. You just make the best of it and keep on going. That’s why I think he was still engaging in life with so much zest when he died at 101.”

The video, “Luck was with Me,” was an outstanding success when first played at Edgewood. The Men’s Club relented and even invited the ladies to attend. They all loved it.

Veterans Services Officer Bruce Siegel praised Charlie’s service during World War II along with the contributions he made to the community.

“Charlie Wills lived a long and great life,” said Siegel. “My wife Candy and I feel blessed to have known him for over 25 years. Charlie was one of the classiest, down-to-Earth, extraordinary men we have ever met. I want to thank him and his daughter for sharing the video with us. I do plan to schedule a future viewing for my fellow Lynnfield veterans. To Charlie Wills, I say: You were a member of one of the greatest generations in our country’s history. Thank you for your service. And thank you for the tremendous contribution you made to the town of Lynnfield.”

Residents can send comments to Helen Breen at helenbreen@comcast.net. To watch the video, visit http://bit.ly/3BgNR5t.